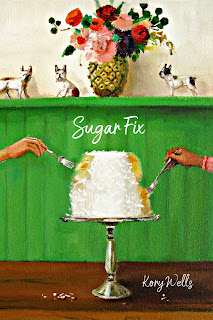

The following is the sixteenth in a series of brief interviews in which one Terrapin poet interviews another Terrapin poet, one whose book was affected by the Pandemic. The purpose of these interviews is to draw some attention to books which missed out on book launches and in-person readings. Ann Keniston talks with Kory Wells about using a central metaphor as an organizing principle, the role of facts and stories in a collection, and the arc of a poetry collection.

Ann Keniston: Sugar is central to your collection, as the book title, Sugar Fix, makes clear. Yet sugar seems to mean different things—at times it’s aligned with desire and pleasure, and at others it’s something to be resisted, an “urge,” in one poem, that the speaker is “unlearning.” Can you talk a bit about how you understand sugar in the collection? How did it become central to the collection? Did its meaning change or become more complex as you worked on the manuscript?

Kory Wells: It’s hard to believe now, but I didn’t know that sugar was going to be such a central motif of the collection for quite some time. I knew I was writing about identity and connection and love, and that I was witnessing to the power of story and memory. I also knew I wanted to incorporate a wider sense of history and social context. But it wasn’t until I wrote “Due to Chronic Inflammation,” which interweaves the speaker’s addiction to sugar with America’s addiction to gun violence, that the bells went off in my head: I can’t tell my story without talking about sugar: red velvet cake, sugar sandwiches, Dairy Queen, marshmallow pies. My ancestors even lived at a place called Sugar Fork! Sugar represents many factual details of my family history. But more than that, for me sugar represents longing: my longing for romance, yes, but more than that, for kinship and connection—even across time and the troubling aspects of our country’s history and present.

Keniston: I noticed that you use the word “fact” several times in the course of the book, often in relation to something you want to amplify or contradict. And then the word “story” also recurs. Can you talk about how you see the relation between those two terms? Are stories a way to correct so-called facts or to amplify or complicate them? Given that many stories are associated with family, especially a grandmother figure, do these stories have the weight of truth, perhaps emotional truth? Or can they also be misleading or deceptive?

Wells: Thanks so much for this question! This tension between stories and facts dominates our entire socio-political climate, right? It’s common to hear someone say, “We need all the facts” and believe those facts tell THE story. But we don’t often hear, “We need all the stories.” And even if we did, how often are we truly open to hearing someone whose story we think we may not like or agree with?

I think that’s what Sugar Fix is attempting to champion, in its own small way—the idea that we need all the stories, and that the best, fullest stories dissolve the line between us and them.

A major thread of this book comes from my obsession with how my family’s oral history jibes—or fails to jibe—with facts I learned from genealogical research and DNA testing. In my experience, the stories my grandmother and other family members told definitely captured some of the truth, and that still matters deeply, even if it’s not the full story.

The facts are that my family traces back to the Catawba, and before that a Saponi tribe, but hearing the story that I was descended from Cherokee who narrowly escaped the Trail of Tears still shapes the empathy and connection I feel today.

The facts are that I’m descended from a woman who was arrested for dancing and masquerading as a man in Philadelphia in 1703. The facts are also that I am of African descent. I can’t say these facts—which are relatively new to me—are life-changing. But they expand my story, and that’s part of what I was writing toward in these poems. How I include new facts in my story, my own self-reckoning, particularly as a person who tries to be intentional about connection and allyship, is, to me, significant.

Keniston: I was really interested in your use of the word “cousin,” first in relation to the possibly-but-probably-not blood relative Gypsy Rose Lee and then as an addressee in several other poems. It seems like part of the book’s project is to destabilize conventional lineage-based ideas of family, as well as race and history. Can you talk a bit about how you extend the notion of family, maybe especially in relation to your use of form, including renewable forms like the villanelle, sonnet, and ghazal? To put it another way, what is the relation of the theme of family to that of political reimagining in the book?

Wells: Oh, thank you for noticing how I address cousins! Perhaps I’m intrigued by the idea of consanguinity because I’m an only child. Or because I grew up in a small town, where people are more connected than you realize, and you have to be careful you don’t bad-mouth your new friend’s second cousin. Or perhaps, amid our national divisiveness, I’m reaching, reaching for common threads.

At any rate, I think my use of form is, in one sense, a nod to the various rhythms that have shaped me as a Southerner with Appalachian roots: a rich storytelling tradition, the cadence of Southern and Appalachian speech, the rhythms of old time and classic country music, the spread of a Sunday soul food dinner, the particularly Southern customs of hospitality and manners. All of these things ignite my sense of kinship.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that, as someone who came to poetry by way of computer science, I have occasionally felt like an outsider to the literary community. I want to be clear: I do feel a deep belonging much of the time—I have so much gratitude for the kinship of fellow writers! But let’s face it—there are a lot of poets, and it can be easy to feel overlooked. By employing poetic form, I think I am, in a small way, acknowledging literary tradition and saying, “I want to belong.”

Keniston: Can you talk about the shape of the book? Your last section title is “As I Already Said, Sugar” and circles back to some of the themes of the first section. Yet things seem different by the end of the manuscript: several of the poems look forward to an uncertain future rather than back to childhood. Can you talk about how you imagined the arc of the book?

Wells: I enjoy reading poetry collections that have a definite arc, so I started thinking about that with my manuscript early on. Initially, for a few years while I was working on the manuscript, I used a James Dickey quatrain—the last lines of “Into the Stone” —divided into four sections as an organizational device. One of my early readers, a novelist friend, said it was “impenetrable,” so that’s when I backed up and started looking at excerpting my own words as section titles. But the Dickey excerpt was still in my mind: this idea of how the dead “have the chance in my body,” and how that interweaves with stories and what we carry, and the comfort of knowing and being known.

In revision, I also faced the fact that my grandmother, who is a definite character in my earlier chapbook, Heaven Was the Moon (March Street Press) and who I thought I was sort of done with, deserved a greater role in framing the collection. “Untold Story,” which is the first poem in section one, and “When the Watched Pot Boils,” the first poem in the final section, were both written relatively late in the process and reflect how I finally came to understand this collection as being all about story.

Sample poem from Sugar Fix

He drove a four-door Chevy, nothing sexy,

but I'd been thinking of his mouth for weeks

when he finally called me up

and asked if I'd like to get

some ice cream.

I was full from supper and my

thighs sure didn't need it, but

I've never struggled with

priorities. That Dairy Queen

had gone downhill even then—

bright red logo faded like a movie star

who's kissed away all her lipstick—

but it still had a drive-in, and he

knew how I was about nostalgia

and sugar. This is how a place

became our song. We parked

under the sun-bleached canopy

and I leaned over him

pretending to read the menu.

Then at his rolled-down window

we confessed our desires

more or less into thin air,

which now that I think about it

sounds a little like church

and believe you me

I'd been praying about him.

How I wanted him.

How if I couldn't have him,

I wanted to be free

of want. Do you get that way

sometimes? Where all

you can think about is

chocolate, chocolate, chocolate,

or in my case man, man,

that man. The bench seat

of his Chevy became a pew,

the space between us palpable

as the early summer humidity.

I kept telling myself

it's just an ice cream,

but even then I knew

love is a kind of ruin.

When those cones arrived

so thick and voluptuous,

I almost blushed to open my mouth

before him, expose my eager tongue.

Kory Wells is the author of Sugar Fix, from Terrapin Books. Her writing has been featured on The Slowdown podcast and recently appears in The Strategic Poet, The Literary Bohemian, Poetry South, Peauxdunque Review, and elsewhere. A former software developer who now nurtures connection and community through the arts, storytelling, and advocacy, Kory mentors poets across the nation through the from-home program MTSU Write and has served as the poet laureate of Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

www.korywells.com

Ann Keniston is a poet, essayist, and critic interested in the relation of the creative to the scholarly. She is the author of several poetry collections, including, most recently, Somatic (Terrapin, 2020), as well as several scholarly studies of contemporary American poetry. Her poems and essays have appeared in over thirty journals, including Yale Review, Gettysburg Review, Fourth Genre, and Literary Imagination. A professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno, where she teaches poetry workshops and literature classes, she lives in Reno, Nevada.

www.annkeniston.com